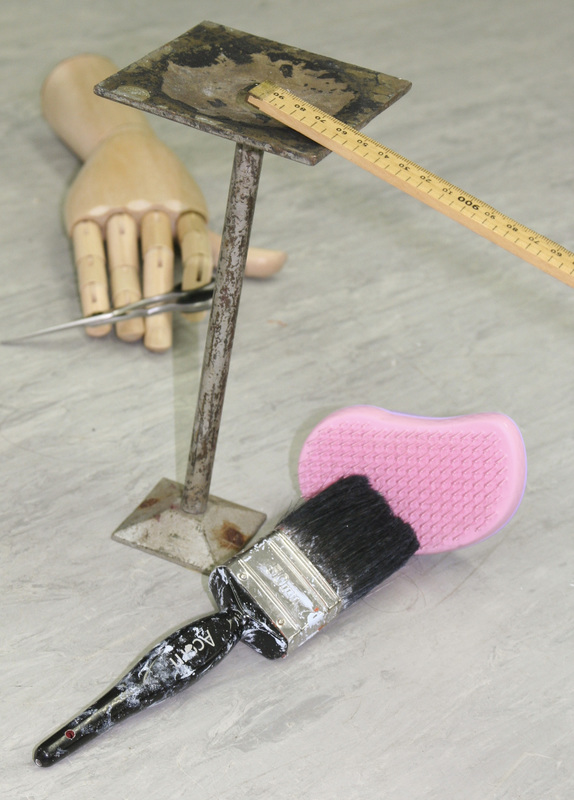

sorhed believe that at the core of practice artists must be able to defamiliarise themselves from the everyday in order to see afresh. They must be able to tolerate ‘not knowing’ where an enquiry might be going in order to see something new. This is not a mindless process; it is a switch to, and an immersion in, a different way of thinking. This re-visioning of reality enables the overlooked to be reconsidered and new understandings to emerge. This principle is embodied in the objects hedsor / sorhed make. The objects are formed from unexpected combinations of everyday items – certain unexpected combinations ‘fit’ or ‘resonate’ with each other. The resultant composite form is something that is not easily knowable or nameable. There is a familiar recognition of elements and at the same time enough unfamiliarity to resist habitual response.

The principles briefly outlined above are indebted to Viktor Shklovsky - they form a backbone to our research, and have many areas of overlap with Brecht's 'Estrangement Effect' (Verfremdungseffekt) (1915) and Freud's 'Uncanny' (1919). There are innumerable examples of these ideas being applied to art forms over the last century and they play a significant part in modernist visual culture. Working as hedsor in musuems and galleries we have repeatedly introduced 'estrangement effects', and have 'made-strange' in material form as we have responded to their collections and themes. Our 'defamiliarised' objects (often combinations of two or more familiar objects) develop out of a well-researched body of knowledge which serve as the parameters of our enquiry. In simple terms, we introduce 'not knowing', doubt, or uncertainty, into learning environments that can at times be dominated by facts, 'knowing' and the 'known'. Tolerating 'not knowing', allowing for thinking to emerge and allowing dialogue and interpersonal exchange offer some kind of counterbalance. The collections of objects we make have visual correspondence to the theme, or body of knowledge they relate to - be that a specific exhibition, temporary exhibition, the architecture of a gallery, the history of an archive.

For Turner Contemporary the parameters for research included, the history of Margate, the geographical surroundings (specifically the sea), Turner's various philosophical enquiries and the key moments of recent art history that influence contemporary art. The views from the gallery are predominantly of the sea with a major shipping lane crossing the line of sight. We picked up the theme of sea navigation by deconstructing a navigational compass - a virtually indestructible globe filled with liquid, the dial of which stayed level no matter how vigorously it was turned. The object looked a large molecule of water and when seamlessly combined with a ladle gives a range of readings that visually resonate with the surroundings. Anybody who is prepared to enter into dialogue around the object starts without the confidence of knowing what the object is, or is for. For those prepared to willingly 'suspend disbelief' (Coleridge 1817) questions emerge, and wondering begins. A skilful facilitator might wonder-out-loud with a learner, peppering facts and knowledge amongst questions, allowing co-constructed knowledge to develop. Rather being told what to learn and to think, learners form questions they may want to explore on their own terms, and they participate in a learning exchange experience.

In our earlier work our objects were exclusively housed as collections in boxes and made in response to specific places or subjects. A colleague coined the name 'Object Dialogue Box' to describe the first box; it remained and for a time defined that element of our practice, as did the name hedsor. Over time our interest has expanded into different contexts. During a period of ten years a gradual change of focus has happened - many more objects have been made away from the museum context. In addition we realised that the valency or punch of an object - the emotional impact - has a significant bearing upon how deeply learners engage. We actively try to develop objects with this kind of potency - they are appropriately unsettling. As a result we have ceased to use the term 'Object Dialogue Box' as it limits and defines too much. Similarly, the change in the approach to making objects sees the term 'hedsor' inverted to become 'sorhed' - we have undergone a practice based turn and the name has taken a corresponding turn.

Coleridge, W. (1817) Biographia Literaria. Chapter XIV. [online] <http://www.english.upenn.edu/~mgamer/Etexts/biographia.html> (accessed 03.09.15)

For Turner Contemporary the parameters for research included, the history of Margate, the geographical surroundings (specifically the sea), Turner's various philosophical enquiries and the key moments of recent art history that influence contemporary art. The views from the gallery are predominantly of the sea with a major shipping lane crossing the line of sight. We picked up the theme of sea navigation by deconstructing a navigational compass - a virtually indestructible globe filled with liquid, the dial of which stayed level no matter how vigorously it was turned. The object looked a large molecule of water and when seamlessly combined with a ladle gives a range of readings that visually resonate with the surroundings. Anybody who is prepared to enter into dialogue around the object starts without the confidence of knowing what the object is, or is for. For those prepared to willingly 'suspend disbelief' (Coleridge 1817) questions emerge, and wondering begins. A skilful facilitator might wonder-out-loud with a learner, peppering facts and knowledge amongst questions, allowing co-constructed knowledge to develop. Rather being told what to learn and to think, learners form questions they may want to explore on their own terms, and they participate in a learning exchange experience.

In our earlier work our objects were exclusively housed as collections in boxes and made in response to specific places or subjects. A colleague coined the name 'Object Dialogue Box' to describe the first box; it remained and for a time defined that element of our practice, as did the name hedsor. Over time our interest has expanded into different contexts. During a period of ten years a gradual change of focus has happened - many more objects have been made away from the museum context. In addition we realised that the valency or punch of an object - the emotional impact - has a significant bearing upon how deeply learners engage. We actively try to develop objects with this kind of potency - they are appropriately unsettling. As a result we have ceased to use the term 'Object Dialogue Box' as it limits and defines too much. Similarly, the change in the approach to making objects sees the term 'hedsor' inverted to become 'sorhed' - we have undergone a practice based turn and the name has taken a corresponding turn.

Coleridge, W. (1817) Biographia Literaria. Chapter XIV. [online] <http://www.english.upenn.edu/~mgamer/Etexts/biographia.html> (accessed 03.09.15)

light switch - Kettle's Yard

light switch - Kettle's Yard

The photograph of the light switch is from Jim Ede's house, Kettle's Yard, Cambridge. The glass-fronted light switch is a low-level example of something that has become defamiliarised - we become more aware of the existence of the electrical circuits in the building. We also are made more aware of the materiality and structure of the building.

|

Examples of relevant published papers

Object Dialogue Boxes: the Unexpected and Unfamiliar as Important Ingredients for the Creative Learning of Children and Young People in Art Galleries By hedsor – Kimberley Foster and Karl Foster, Joanne Davies 5 March 2014 http://www.tate.org.uk/research/research-centres/learning-research/working-papers/object-dialogue-boxes This paper is part of a series that are from or in response to presentations made at the Worlds Together Conference at Tate, 2012. The importance of the unfamiliar and unexpected in creative teaching,interpretation, and learning. p.106 What is research-led teaching? Multi-disciplinary perspectives. Published (2010) by CREST / GuildHE, edited by Alisa Miller, John Sharp and Jeremy Strong http://collections.crest.ac.uk/5215/1/CREST_What_is_research-led_teaching_web.pdf the image of the paintbrush, mannequin hand, ruler, scissors, and metal stand is not a consolidated work. It came about through playful dialogue with a learning group. Characteristically, there is a chain of equivalences or resonances between the objects which could easily be developed.

|